- Home

- Dalia Roddy

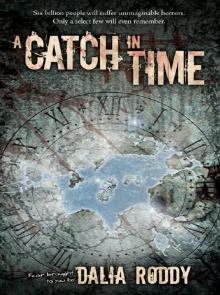

A Catch in Time Page 4

A Catch in Time Read online

Page 4

Flat on his back, he couldn’t move. He gasped, sucked in a lungful of pain. He heard fists on flesh, the clatter of something, the thump of a body near him.

He had to get up, help Josiah. Sparkling pinpoints danced across his vision. He propped himself on his trembling arm and blinked. So dark out. Something vertical next to him. Legs, in jeans. Dull noises, shouts. His blurry vision traveled up the legs. Who? A fist curled around … a gun.

“NNNOOOOO!” The word exploded from him. With all his weight, he flung his arms around the legs, and lunged. He heard the knee next to his ear snap, heard a blast. Not Josiah. Please— Still down, he slammed his fist into the groin of the person with the gun.

Josiah’s booted foot flashed by, slamming into the downed man’s head, which snapped sideways, gruesomely disfigured. Then, silence.

Eli sat up and pressed his hand against his head. Even with new bruises and pains, his headache still pounded.

“Eli, you all right, man?” Josiah asked. He squatted to look in Eli’s face.

“Are they gone?”

Josiah nodded. “Yeah, they took off.” He glanced at the body next to them. “This one, he’s as gone as they get.” He surveyed the dark street. “Can you get up? We need to move.”

With Josiah’s help, Eli shakily rose.

“My first fight,” he said.

“I figured,” said Josiah, with a gentle punch to Eli’s upper arm. “You done good, man.”

Eli looked at the broken plate glass of the storefront where they stood. The three men who’d jumped them had come out of there. Probably looting, just like Josiah and him. Like everyone.

“Is the kid okay?”

Josiah shrugged and Eli limped over to the teenager sitting in the tangle of his bicycle.

“You okay?”

“Yeah, I think so.”

Eli asked a few questions, just enough to learn that the boy, who’d cycled by at just the wrong moment, was alone and scared.

Eli turned to Josiah. “Alex needs to come home with us.”

Josiah looked hard at Eli, shook his head, then sighed. “Let’s go,” he said, picking up the gun.

CHAPTER 8

JOHN THOMAS HAD NEVER KNOWN SUCH SADNESS. HE fought it, was overwhelmed by it. He lay in his bed and stared at the mobile of the solar system above his head: the sun, surrounded by all nine planets. He focused on the earth and tried not to hear Lucas rummaging through the cabinets in the kitchen beneath him.

A plate clattering onto the tile counter, the jangle of the silverware drawer opening. The refrigerator door—bottles clinking dully in its shelves—thudding shut. He sat up, feeling dizzy. His stomach felt empty. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d eaten. He didn’t know how long he’d lain in his bed, only that time had passed, that he had slept, woken, slept; he felt sick and miserable awake, and nightmarish asleep.

Light-headed, he pushed his blankets aside and slowly put his feet on the floor. He had his shoes on. And he was wearing jeans. He walked to the bathroom on shaky legs, thirst filling his mind. He bent to the faucet. Water had never tasted so good.

Removing his clothing, he walked to the closet. Sounds from below had ceased. John Thomas selected clean clothes. He hated being dirty. He would have to change the sheets. He had often helped his father change bedding. A memory of his father, tossing one end of a sheet to him as they both hovered over his bed, caused tears to well. He squeezed his eyes shut. He would not think about his father now, he would not.

Freshly washed, dressed, and with brushed teeth, John Thomas descended the stairs, gripping the banister tightly. Familiar sights of his home: the throw rug in the foyer, the coat tree by the door, the photos on the walls. Thoughts without words. He paused in the kitchen doorway. Lucas sat in his usual chair, eating from a bowl obscured by clutter on the table: cereal boxes, dirty dishes, ketchup. The mess extended throughout the kitchen, plates lumped with congealed scraps, dirty glasses, gaping boxes, empty cans. Only the sink was clear.

“About time, John Thomas,” Lucas complained. “We hafta go to the store and there’s no TV and there’s no hot water and the flashlight stopped working. And you just kept sleeping and I almost got lost when I tried to find the store. We’re out of Fruit Loops, John Thomas, and I hate this stuff.” He smacked a cereal box in front of him with his spoon, arcing droplets of milk through the air.

John Thomas took two slices of bread from a loaf on the counter, put them in the toaster, and pushed the lever down. He stared into the slots, waiting for the red glow.

“It doesn’t work,” Lucas said through a full mouth. “Nothing works, haven’t you been listening to me? You need to call the ‘lectric man, except the phone doesn’t work either. He needs to fix the TV, too, I been missing things. It’s not fair, John Thomas, it’s very, very bad. You should get mad at him.”

John Thomas popped the cold bread out of the toaster, put the pieces together, took a bite, then another. He was so hungry.

“It’s not his fault, Lucas,” he said, emulating his father. His father had always explained everything.

Lucas frowned mutinously. “Well, somebody broke it. Then it gets night and there’s nothing to do. I don’t like it. We need TV and lights and Fruit Loops, John Thomas.”

Lucas thought about telling John Thomas about his nightly adventures into the chaotic streets but decided against it. John Thomas might not let him do it and then there would be nothing to do. Even his nighttime prowling had become less interesting. Grown-ups were clearing things away, and there weren’t nearly as many dead people so it was harder to find and watch the dogs feast.

“Oh! John Thomas, let’s go back to the bridge.” Lucas had been wanting to explore the carnage he remembered but knew he couldn’t find his own way back there. Although he didn’t expect John Thomas to agree, he hoped for it. So many things were different, now. Maybe even John Thomas.

John Thomas chewed his dry bread and swallowed. He looked through the cupboard for a clean glass but couldn’t find one, so he picked the least offensive glass off the counter, rinsed it, filled it with cold water, and drank.

Lucas was still waiting.

“The bridge is too far away,” John Thomas said. He could remember little of their journey afoot across the Golden Gate. Most memories were obscure; a twist of dented metal, a bumper he’d grasped for leverage, a tire he’d used for a boost, a broken window crunching beneath his foot. But one image overwhelmed all others: his father, under the dashboard, neck twisted, eyes sightless.

Dark pain congealed around his heart. His eyes lost focus and he flinched at a sudden tug on his hand, jerking it away and staring, startled, at Lucas.

“Let’s go,” Lucas said.

“I told you, it’s too far.”

“No, to the store. I finished the milk. Let’s go to the store and then let’s find the TV man.”

John Thomas unhooked their jackets from the coat tree. He helped Lucas put his on, then donned his own and slipped the house key chain around his neck. They stepped out into a cold drizzle.

He needed to find someone to help them, to take care of Lucas, and to help him—John Thomas—understand what was happening. A grown-up would know. Mrs. Johnson, up the street, maybe. She would wrap him in her plump arms after he told her what had happened to his father. She would call him “honey.” Blinking back tears, he hurried down to the sidewalk, Lucas in tow. They would go to Mrs. Johnson’s house. He could already almost feel her cushiony safety.

Cars had jumped a curb and were entangled against a brick building, obstructing the sidewalk. John Thomas focused on Mrs. Johnson’s house, a three-storied structure of white stucco overlaid by geometric designs in dark timber. Once there, he stepped onto the stoop, pulling Lucas along with him.

“John Thomas? Is this where the TV man lives?”

“Shh. No. Mrs. Johnson lives here.” John Thomas rang the bell, then peered through one of the beveled glass windows bracketing the door. A gathered lace curtain hung

against the window inside, preventing him from seeing anything other than vague shadows.

“Does she have Fruit Loops? Is that why we’re here?”

Ignoring Lucas, John Thomas rapped his knuckles against the window. Maybe the doorbell didn’t work. Maybe she’d gone out, or maybe she was in her backyard, with her flowers and fruit trees. John Thomas walked to the side of the house where a high wooden gate barred entry to a walkway leading to the back of the house. Lucas followed.

The gate opened with a latch, but John Thomas felt suddenly uneasy and glanced behind him into the eerie fog. Nervously wiping beads of drizzle off his cheek, he depressed the latch and pushed the gate wide enough for the two of them to slip through. The rattle of the latch falling into place behind them sounded unnaturally loud.

As they walked single file along the narrow walkway between the house and the high wooden fence, John Thomas was assaulted by a terrible, unfamiliar odor. He cupped his hand over his nose in disgust.

“She must be dead, too, John Thomas,” Lucas said matter-of-factly, recognizing the odor from his nightly prowling.

Startled by his loud voice, John Thomas whirled around. “Hush up, Lucas,” he whispered harshly. “You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Lucas smiled, happy to discover he knew something that John Thomas didn’t. He liked to surprise—no, to shock. When John Thomas had come down the stairs this morning, Lucas had told him all kinds of new things, but John Thomas hadn’t reacted at all. But this reaction. Oh, boy, this reaction was more like it!

“I do too know,” he trumpeted. “She’s dead. Lots of people are dead.”

John Thomas hurried along the walkway. The smell was making him feel sick again. He finally reached the end of the house, and the garden spread out before him, nothing like he remembered it. The fruit trees stood bare of leaves, the rose bushes held no blooms. The central fountain was empty of surrounding flowers. Only bordering camellia bushes and a profusion of calla lilies in one corner provided greenery.

Mrs. Johnson lay sprawled on the hard ground near the calla lilies, her body hideously bloated and distorted.

Lucas hurried in front of John Thomas so he wouldn’t miss his expression. “I told you, John Thomas. I was right. I told you she was dead, and she is.”

John Thomas shoved his hand hard against mouth and nose.

“Shut up!” he shouted, his voice muffled by his hand. “Shut up, shut up, SHUT UP.” He almost smacked Lucas. And why shouldn’t he? There was no one to stop him now, no one to say, “Don’t ever, ever hit your brother again.”

Trembling, John Thomas turned from Lucas and ran to the back door, pushed it open, bolted through the kitchen and the long hallway, into the foyer, and to the front door. Gasping for air, hands on his knees, his small back rounded, the weight of his thoughts crashed down on him.

What should he do now? Was everyone dead? Were only he and Lucas left? Hot tears swam in his eyes and he collapsed onto the floor. Huddling against the front door, he cried with choking awful noises, his body rocking furiously in time with his sobs.

Then he heard the music. It came in choppy notes. He gulped himself into silence, straining to hear. Yes, it was music, music coming through the door. People. He scrambled to his feet, grasped the brass doorknob, and fumbled with the deadbolt. A click. A turn.

A small body squirmed forcefully between him and the door.

“No, John Thomas, don’t,” Lucas said in a loud whisper. “They’re bad people, very bad people. I saw them before, they’re taking kids away, John Thomas, all of them. They’re going into houses and taking kids,” Lucas whispered as fast as he could, desperate to keep his brother from opening the door.

It was true, Lucas had seen those grown-ups before, and he’d hidden from them. From hiding, he’d watched them go into two houses and come out with frightened children.

Lucas didn’t want to be taken from his house, from his newfound freedom. He was determined to keep John Thomas from letting the grown-ups in. They would wreck everything, make him do things he didn’t want to do, watch him all the time.

Lucas leaned into John Thomas’s face. “They’re probably eating the kids, John Thomas, cooking them and eating them.”

John Thomas blinked numbly at Lucas, unsure if he’d heard right. Overwhelmed by grief and loneliness, he felt dazed. His head hurt and his nose was stuffed.

Lucas looked at John Thomas’s tear-smeared face. He needed to see shock and surprise. So he embellished his story. “They were crying, John Thomas, and the people told them to shut up and they shook ‘em and shook ‘em and took ‘em away.” Lies came easily to Lucas, and, focused on keeping John Thomas from opening that door, the story became his reality. “They’re very, very bad people.”

John Thomas stared at his brother. Could it really be true?

“Don’t ever go anywhere with an adult you don’t know, John Thomas.” His father’s warning, repeated often, boomed through him. He could almost hear his father’s voice. “There are bad people out there, John Thomas, bad people who do terrible things to little boys. Promise me that you will never go anywhere with a stranger.”

The music filtered through the door. The people out there playing the music were strangers, maybe the very strangers his father had warned him about.

He remembered asking his father what the terrible things were that such people did to little boys, and his father, who’d answered every question, hadn’t answered that one. He’d wondered what could possibly be so bad that his father wouldn’t talk about it.

Now he knew. Horror cramped his stomach. They eat children.

The music was passing right outside the door now, the notes a caricature of melody, a trap, like candy, or a request for help. It was the music of children-eaters.

Lucas, satisfied with John Thomas’s shock, hissed, “We gotta hide.” He turned and ran to the stairs.

John Thomas watched Lucas pound up the stairs. The terrifying music, so loud. With a sudden jerk, he ran after his brother.

Three flights of stairs left them breathless. Lucas plunked down on the last step and watched his brother clamber up to stand, gasping, over him. The attic ceiling sloped steeply. A short hallway had a door on either side. Before them, a curtained, mullioned window faced the sky, three stories above the street.

John Thomas didn’t think his heart could pound any harder. The street below, so empty ten minutes earlier, was suddenly loud with noise. Engine sounds. Voices. The terrible music.

“It’s them,” Lucas said. He scrabbled on hands and knees and peeked out from one lifted corner of curtain.

John Thomas dropped to the floor. Terror freezing his insides, he couldn’t sound a warning, Get away from the window. They’d see him and come into the house.

His fear was so huge, so real, his still-fresh grief and loneliness so raw and overwhelming, that it was harder to have faith in the old reality than it was to tumble headlong into nightmarish possibilities.

He forced himself to crawl over to Lucas, to reach up and grab the back of his shirt and yank him down.

Lucas fell hard, twisted around, and punched out with a small fist. It landed on John Thomas’s thigh.

“They won’t see me,” Lucas spat.

He persuaded John Thomas that they should keep an eye on the enemy, so, together, they very cautiously peeked out.

It looked like something from a horror movie. Frenzied people, faces covered with masks, scarves, bandannas, sprinted into houses, and came out with arms full of things they stuffed into cars. Then it shifted, from robbing and looting to dark insanity.

Some dragged bodies out and threw them in a pile in the middle of the street. Others doused the pile with liquid and threw lit matches onto the heap. Flames exploded upward. Neither brother could tear his eyes from the insatiable flames.

The bodies writhed in the heat: a shifting leg, a curling arm, a jerking head. Terrified, John Thomas mistook the movements, thinking the people alive as he wa

tched the malevolent flames leap in gaseous colors, shriveling clothes, igniting hair, blistering and blackening skin.

Was this how they cooked children? Moaning, he backed away from the window.

Then came the sound of banging on the front door.

John Thomas grabbed Lucas and darted into a storage room on the left of the short hallway. Yanking open a closet door, he shoved Lucas before him until they were both deep into a dark corner behind stacked boxes and hanging coats smelling of mothballs.

John Thomas’s heart raced. He was now convinced that his brother was right and that his earlier warning had saved them from those very strangers his father had warned him against. A searing ache of longing shot through him and he wished with all his might for his father’s return, for an end to the terror, the aloneness.

He heard voices in the house. Faint at first, but getting louder, closer. Then heavy footsteps on the nearby flight of stairs. The door to the room crashed open. He held his breath. Any second now, the door to the closet would be flung open, their hiding place revealed. But the heavy tread receded, the stairs creaked, fainter now. The slam of the front door.

Breathing hard, too scared to move, he strained to hear.

The smell of mothballs was strong. Darkness, odor, and only two sounds, his own and Lucas’s breathing. Lucas’s small body pressed against him, the only familiarity left, mingled with tentative quivers of relief. His brother’s actions, keeping him from opening the front door, blended with his father’s warnings, his father’s essence of loving protection. For the first time in a long time, he felt stirrings of affection toward Lucas.

Warmth for his brother began to fill the cold black hole in the very center of him. His mind, unwilling to endorse a brother both good and bad, aligned itself with the more comforting idea of the good brother whom his father had loved. And as his mind retreated from the edge of a chasm of which he was only dimly aware, distancing itself from the dread that had once proscribed his relationship to Lucas, he felt only welcome relief.

Watch out for Lucas, his father had said. John Thomas could still hear his voice as he’d uttered those last words. New purpose and strength flowed through him. He would protect Lucas, just like his father had told him to do.

A Catch in Time

A Catch in Time